If you haven’t noticed, all your favorite tech stocks are taking a nose dive. What gives? Something very simple that you learn when you become a financial professional: the discounted cash flow model, or DCF.

There are two traditional ways to value a company. You could compare that company to other similar companies, which are called comparables or comps. This is known as relative valuation. It’s like when you want to value the price of a home: Compare its price-per-square-foot or other factors to recently sold homes in the area, and this will give you a relative price regardless of its intrinsic value.

Another way to value a company is to find the price of the cash flows generated by this company in the future, and discount them back to today. This is the DCF. Of course, a good DCF includes comps, but it also includes many other factors. Think of valuing a home based on its size, location, finishes, and more.

The most important factor for valuing a company, after estimating cash flows, is the discount rate. Think about the discount rate like this.

Imagine someone could give you $1,000 today or $1,000 a year from now. Which would you choose? If you’ve had a finance class before, you’d choose $1,000 today. Why? Because you can invest that money in the market and make more than $1,000 a year from now. How much more? Well, depends where you invest it, but that number is basically the discount rate.

To create a valuation model for a company, the first step is to estimate how much cash you think this company will create for each of the next five years or so. Add those up, and discount that cash flow back to the present using your discount rate. Voilà—that’s how much the company is worth today. (Of course, a DCF is much more complicated than this.)

One of the most important components of the discount rate is the interest rate. That’s because interest is the cost of borrowing money. So, if your company has a lot of debt on its balance sheet, like tech companies, interest takes more of an effect, which reduces the overall value of the company. This is known as the weighted average cost of capital, or WACC.

Now let’s zoom out.

During the pandemic, the government released tons of money into the financial system, helping individuals and businesses get through the dark times. However, based on the quantity theory of money, this causes prices to rise over time, which is also known as inflation. The value of tech stocks went through the roof partly due to this and partly due to everyone working from home. And partly due to Robinhood—remember Gamestop? Exactly.

So, to reduce inflation, the Federal Reserve, our nation’s central bank, needs to raise interest rates. Why? Because that would make it more costly to borrow money, whether as a business to invest or as individuals to buy a car or home. This reduces lending and hopefully prices.

But remember, according to the DCF model, if you raise interest rates, that lowers the value of the future cash flows, making businesses less valuable today. As investors read the mind of the head of the Fed, Jerome Powell, they began to re-price the value of companies, especially high-growth, debt-laden tech stocks.

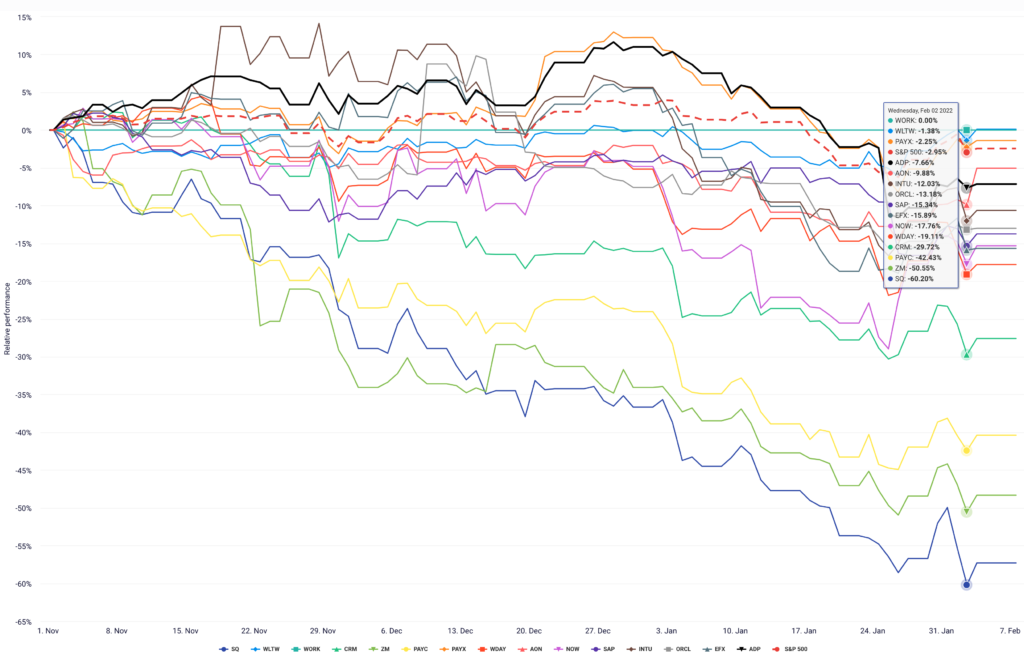

Since high-growth tech stocks don’t turn a profit for a long time, they’re financed with hope and debt. Again, this means that their cash flows far into the future are more sensitive to interest rate rises than other kinds of companies. So, a rise in interest rates means tech stock charts, like those for work tech, look like this:

So, now you know the basics of what the market is doing. Will this spill over into venture capital and private equity, which have had record-shattering years? Probably. The mechanics of valuation are the same, whether for public or private companies, because the mechanics of money are the same. A dollar is a dollar is a dollar.